Blending influences from afar

Blending influences from afar

244 comments

Today we think of Ireland as the island located on the north-western shores of Europe. During the early medieval period however, the country’s cultural borders were far less clearly defined, and although its inhabitants considered themselves as living at the ‘edge of the world’, they were anything but isolated from it.

With the gradual collapse of Roman Britain in the late fourth and early fifth centuries, small Irish settlements sprung up along the western seaboard of Scotland, south Wales and north-west Cornwall. Other Irishmen paid shorter visits to Britain, capturing Romano-British and bringing them back to Ireland as slaves.

The most famous of these was the Welshman Patrick, later St Patrick, who is credited with forming one of the earliest Christian communities in Ireland during the mid-fifth century.

Fig 1. St Patrick. Clonmacnoise cathedral, Co. Offaly, c. 1460 Photo: Rachel Moss.

Fig 1. St Patrick. Clonmacnoise cathedral, Co. Offaly, c. 1460 Photo: Rachel Moss.

Other Christian preachers, such as Palladius, probably came from further afield, bringing with them the books and other objects necessary for Christian worship.

Schools established at some of the larger church settlements in Ireland became famed for their scholarship and attracted clerics and nobles from across Europe. According the late seventh-century historian, Bede,

‘the Irish welcomed them all gladly, gave them their daily food, and also provided them with books to read and instruction, without asking any payment’.

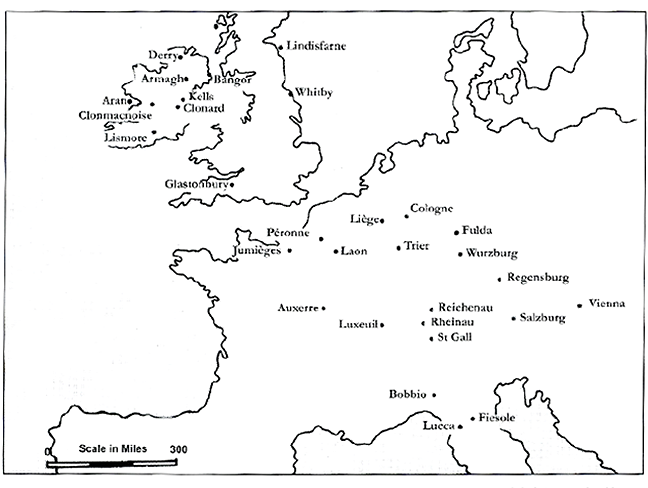

The faith and confidence of Irish Christians developed and Irish missionaries took to the seas and rivers of Europe, establishing a network of church-focused settlements at places such as Iona in Scotland, and across continental Europe at places such as Luxeuil (Burgundy, France), St Gall (Switzerland) and Bobbio (Italy).

Fig 2. Map of Irish monastic foundations in Europe. © Liam de Paor.

Fig 2. Map of Irish monastic foundations in Europe. © Liam de Paor.

Over time, the monastic foundations they established retained elements of their Irish identity, both as a way of memorialising their founder saints and because they continued to welcome clerics and pilgrims from Ireland.

As the fame of Irish scholarship grew, Irish teachers and thinkers were also invited to join centres of learning at schools established in royal and aristocratic courts and large monasteries, so that by the ninth century, the German monk and scholar, Walafrid Strabo remarked:

‘The Irish nation, with whom the custom of travelling into foreign parts has now become almost second nature’.

Fig 3. St Columbanus and St Gall on Lake Constance. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 602, p. 33. cc

Fig 3. St Columbanus and St Gall on Lake Constance. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 602, p. 33. cc

Far from being an inward-looking, insular culture, the books and art created within the environment of the Irish church reflects a learned, global outlook.

The Book of Kells draws deeply from this well of learning, blending together influences from many different places in a uniquely Irish manner.

© Trinity College Dublin

The context from which the Book of Kells emerged was, without doubt, a religious one, at a time during which there was a flourishing of learning and artistic creativity within the Irish Church. However, this does not fully explain the motivation that lay behind such a massive undertaking. As we will see in Week 2, the investment required to make a manuscript of the scale and intricacy of the Book of Kells, both in terms of materials and man-hours, would have been daunting.

To quote the Irish writer Flann O’Brien:

“Could Henry Ford produce the Book of Kells? Certainly not. He would quarrel initially with the advisability of such a project and then prove it was impossible”.

So what was the motivation behind the project, and who was the brains behind it? Certainly since the eleventh century (and doubtless much before that) the manuscript held a strong association with St Colum Cille, a saint renowned for his talents as a scribe.

- One suggestion is that the manuscript was made to coincide with the creation of a new shrine for the saint on Iona in the mid-eighth century; just as the comparable Lindisfarne Gospels were probably created in tandem with the new shrine of St Cuthbert some fifty years earlier.

- Alternatively, it may have been made to commemorate the bi-centenary of the saint’s death in 797. The exact circumstances are tied into the manuscript’s date, which is still a matter of some debate.

By this period it was not uncommon for high-status individuals in both sacred and secular worlds to commission lavish artworks for the Church. This served the dual role of demonstrating their piety, and creating a permanent reminder of their power and generosity in a sacred object displayed in the church. For example, when precious chalices and shrines were stolen from the altar at Clonmacnoise in 1129, they were described not by their appearance, but by the names of their donors.

Fig 1. Panel on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnoise (c. 909-16AD) thought to show king Flann, the patron (right), and abbot Colman of Clonmacnoise (left) marking the act of royal patronage of the site. Photo: Rachel Moss

Sometimes details of the donor are recorded in a colophon – an inscription recording details of the making of a book, occasionally at the start, but typically at the end. If such a record existed in the Book of Kells, unfortunately it was lost along with the ten or so folios now missing from the start and finish of the manuscript. Surviving manuscripts roughly contemporary with the Book of Kells suggest that the abbot of a monastery often played a vital role. In the case of the Book of Armagh (c. 807AD) the book was made for Abbot Torbach by the scribe Ferdomnach and others, while the MacRegol Gospels were written and illustrated by the abbot of Birr c. 820AD. In this context, it is worth noting that on his death in 802, Connachtach, abbot of Iona was described as a ‘choice scribe’.

Whether Connachtach had direct involvement or not, significant resources would have been required. By the latter half of the eighth century, Iona had become a place of pilgrimage for some of the greatest Irish leaders. These included Niall Frossach, king of the Cenél nEógain (a branch of the O’Neill family who ruled over much of north-west Ireland and claimed shared ancestry with Colum Cille) and Artgal, son of Cathal, king of Connaught (the west of Ireland), both of whom spent their last years there. The land at Kells was almost certainly gifted to the fleeing community of Iona in the early ninth century by the Cenél nEógain who owned much of the territory in the area. It seems likely therefore, that while the Book of Kells was the work of religious men, its creation was most likely enabled by the secular powers of the day.

In the comments section below

- What circumstances do you think might have led to the commissioning of a manuscript like the Book of Kells?

- Consider religious, economic or societal circumstances in your comment.

Postar um comentário