Changing meanings The Arrest of Jesus Christ Exhibiting the Book of Kells

At the beginning of the course, we asked the question why almost a million people visit the Book of Kells every year. Over the past three weeks, we've looked at its background, how it was made, and some of the meanings that its creators may have intended in its art. But does this really answer the question why so many people of different nationalities, age, and faith make the pilgrimage to come and see the Book of Kells every year? One of the remarkable aspects of the book is its age. At almost 1,200 years old, its survival in itself is miraculous. Over time, the meaning and values of the Book of Kells have changed.

Up until the mid 19th century, the Book of Kells was visited only by a small elite of biblical scholars. That was all to change in the mid 19th century when it began to be put on public display for the first time. We're all familiar today with the concept of influencers, people who promote a particular product or trend. In the mid 19th century, the ultimate influencers were Queen Victoria and her husband Albert. In both 1849 and 1853, the couple visited Dublin, and on both occasions came to the library of Trinity College to view its collection of manuscripts. Writing in her diary of 1849, Victoria singled out the gospel book of Columcille for particular comment.

From that time, the popularity of the manuscript grew and it became a must-see for both Irish and visitors to Dublin alike. The mid-19th century was also a time of reawakening of interest in history -- in particular, national history. The book of Kells, dating to a time before the anglo-Norman invasion, was seen as being an expression of pure Celtic, or Irish, art. As such, it joined with the shamrock, the round tower, the Celtic cross, and the Irish wolfhound as a symbol of Irishness, becoming particularly popular with the Irish diaspora, those who had emigrated to America and beyond.

Over time, the religious symbolism of the imagery of the Book of Kells gradually transformed, becoming as much a symbol of cultural allegiance as of faith. The Book of Kells holds resonance for more than just the Irish and Irish diaspora. The almost magical quality of its intricate illuminations and its great age place it far away from the contemporary world. Just as the otherworldly appearance of Skellig Michael, the almost contemporary church settlement that now has become Planet Octu of Star Wars fame, so too the Book of Kells has provided inspiration for fiction and science fiction. It's the pages of the Book of Kells on which Martian history is documented in one Marvel comic.

It also provides the centre point of the cartoon the Secret of Kells, which tells a different dreamlike story of the creation of the manuscript. George Bernard Shaw's description of Skellig Michael as an impossible, incredible, mad place, part of our dreamworld, is equally applicable to the Book of Kells. The Book of Kells now holds more meanings than it was ever intended. This creates particular challenges. How should it be displayed? What stories should be told about it? How does one provide access to the growing numbers of people who want to visit it? These are some of the things that we'll be exploring this week.

Changing meanings

101 comments

This week we will be looking at the more recent history of the Book of Kells.

For much of its early life in Trinity College the Book of Kells was only visited by a small elite who had a particular interest in biblical studies. But that was all to change in the mid-nineteenth century, when it began to be made available for the wider public to view.

Growth in nationalist sentiment, coupled with the fashion for revivalist jewellery and luxury items saw the reproduction of motifs from the manuscript on a range of goods, and so its fame began to spread worldwide. Its almost ‘magical’ appearance also proved a muse to artists and writers alike and over the past couple of centuries it has provided inspiration for a very wide range of art and literature.

Don’t forget to consult the glossary which explains some of the key terms used in the course.

© Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin

Felicity O'Mah

ony is assistant librarian in the Manuscripts and Research Library here at Trinity College. Among other things, her work includes the curation and presentation of the Book of Kells to the wider public. Working with the Book of Kells has been probably the greatest privilege of my career working here in the library. It's been, in a way, like serving an apprenticeship, a lifelong apprenticeship, because every day, you're learning something new about the manuscript, everything from its historical background to the imagery behind the decoration. It's an ongoing, lifelong learning process. The story of Kells never really stops. Part of my earliest training with the Book of Kells was learning how to handle it properly.

When I was first given the responsibility of turning the page in the Book of Kells, I can remember the absolute thrill of touching the manuscript for the first time. My heart was literally pounding in my chest, and I really had to focus on just keeping my hands steady while I very slowly and very carefully turned the page. And really that sense of awe never goes away. Well, the Book of Kells is made from calfskin, which we call vellum. And that material, it really doesn't always behave the way you want it to or expect it to. It can react very quickly to the environment it's in.

So every time we prepare to turn the page in the Book of Kells, we have to work in a pre-conditioned, very controlled environment. So what we're looking for is a constant humidity, constant temperature, very low light level, so there's no light damage. We're looking for as relaxed a state for the pages in the Book of Kells, so they're absolutely in their optimum condition. Contrary to urban myth, the page of the Book of Kells is not turned every day nor every week. In fact, we change the page about eight times every year. And this limits the physical handling of this precious manuscript, which is much better for its long-term preservation.

Because the Book Of Kells is so ancient and really quite fragile, scholars have had very limited access to the manuscript over the years. And one of the most important developments in recent times was the production of the first complete full-colour copy of the Book of Kells. And this work was carried out by a Swiss publishing house called Faksimile Verlag Luzern in 1990. And it took over two years for the Swiss team to complete the work of imaging every single one of the 680 pages and then comparing those images to the original in the Book of Kells.

And one of the greatest challenges for the Swiss team was capturing the colour of the vellum because that varies quite considerably, really, from one opening to another in the manuscript, particularly the more famous pages in the Book of Kells that would have been exposed to light over several centuries. These are considerably darker than the pages of text that have very little decoration and wouldn't have been exposed to light quite as often. Following on from their production of the facsimile, in 2013, the images that were used were rescanned within the library by our own photographers.

And these are now freely available online on the college website, so that everyone can spend time looking at the pages in the Book of Kells and poring over the detail. And this resource allows you to magnify details, to zoom in, to zoom out, to move easily from one page to another. And it really leaves you with a greater appreciation of what these monks achieved back in the ninth century.

We look at the privilege of curating the Book of Kells. Looking after a manuscript of this age and fragility presents its own challenges, particularly in relation to the conditions under which it needs to be displayed.

In the past this has meant very limited access to the manuscripts for scholars. This changed in 1990 with the production of a new facsimile of the manuscript. In more recent years photography of the manuscript has been digitized and published online, allowing all to look at the details in the book.

© Trinity College Dublin

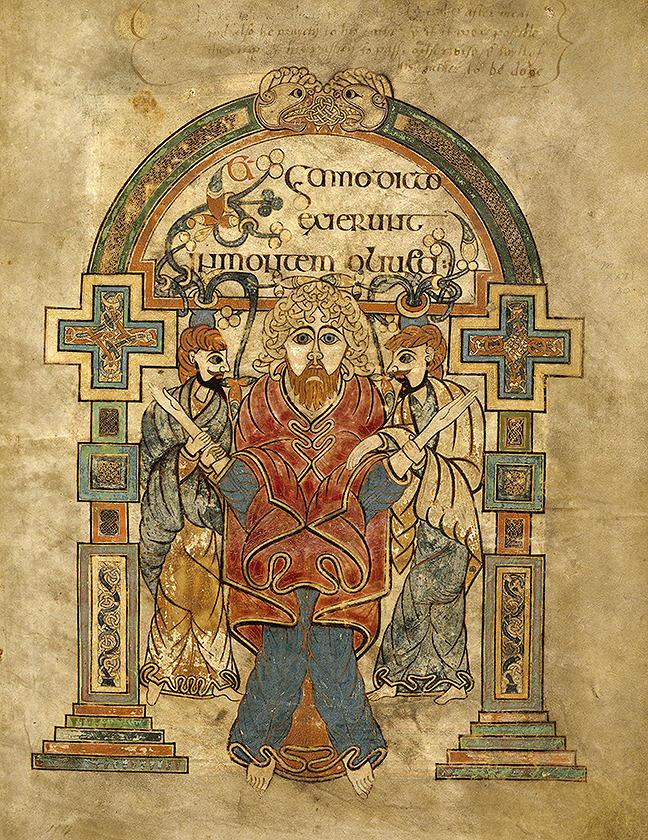

Fig 1. Image of ‘the Arrest’ on folio 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 1. Image of ‘the Arrest’ on folio 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

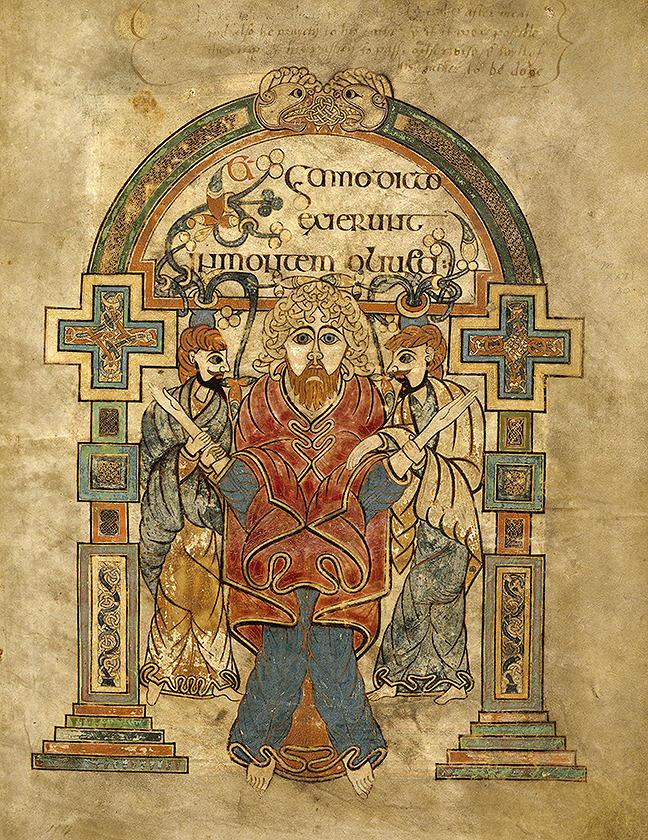

, a pillar decorated](https://ugc.futurelearn.com/uploads/assets/08/a2/hero_08a2c590-e742-4613-9efa-cd8de2c714a4.jpg) Fig 2. Detail of the pillar decoration with chalice and vine in fol. 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. Detail of the pillar decoration with chalice and vine in fol. 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Located among the pages of the Gospel of Matthew, the full page illustration on fol. 114r has traditionally been interpreted as an image of the arrest of Jesus Christ in the garden of Gethsemane as recounted in Matthew 26:47–52 – the start of events that were to ultimately lead to Christ’s death.

Fig 1. Image of ‘the Arrest’ on folio 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 1. Image of ‘the Arrest’ on folio 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.47 While he was still speaking, Judas came, one of the twelve, and with him a great crowd with swords and clubs, from the chief priests and the elders of the people. 48 Now the betrayer had given them a sign, saying, “The one I will kiss is the man; seize him.” 49And he came up to Jesus at once and said, “Greetings, Rabbi!” And he kissed him. 50 Jesus said to him, “Friend, do what you came to do.”[a] Then they came up and laid hands on Jesus and seized him. 51 And behold, one of those who were with Jesus stretched out his hand and drew his sword and struck the servant[b] of the high priest and cut off his ear. 52 Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back into its place. For all who take the sword will perish by the sword.

However, the illustration is not quite that straightforward. It is located five pages before the episode is told in the text and there are a number of elements that are not easily explained as representing this particular scene.

The two figures grabbing Christ’s arms are dressed not as Roman guards, but as priests. They also appear to have plants sprouting from their heads. In addition, there is no sign of Judas, one of the key figures in the story, who is almost always featured in illustrations of it.

The words inscribed above Christ’s translate as: ‘when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives’. This is the sentence that concludes the account of the Last Supper in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 26:30), an event that happens earlier than the arrest.

Christ’s arms are depicted in a very strange, almost wooden manner, and appear to allude to an X-shaped cross. The idea of the cross is further strengthened though the use of cross-shapes in the frame.

The decoration of the base of the pillars that support the frame incorporates chalices with sprouting vines.

, a pillar decorated](https://ugc.futurelearn.com/uploads/assets/08/a2/hero_08a2c590-e742-4613-9efa-cd8de2c714a4.jpg) Fig 2. Detail of the pillar decoration with chalice and vine in fol. 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. Detail of the pillar decoration with chalice and vine in fol. 114r. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Taking all of these elements into account scholars have suggested that this image was intended to recall not just a single event in Christ’s Passion (the term given to the events leading up to and including Christ’s death), but to the idea of his sacrifice more generally.

Depiction of the two priests may be intended to recall the Old Testament passage in Zechariah 2:12-14: ‘What be these two olive branches which through two golden pipes empty golden oil out of themselves? …These are the two anointed ones that stand by the Lord of the whole earth’

The use of the cross motif recalls the manner of Christ’s death by crucifixion on the cross. While the chalices reference the Eucharist – the continued celebration by Christians of the life, death and resurrection of Christ.

© Trinity College Dublin

Postar um comentário