The Book of Kells in literature

The Book of Kells in literature

191 comments

The text of the Book of Kells is a copy of the four gospels in Latin, so not an ‘original’ work of literature. However, the almost magical quality of the manuscript, as a material object, has provided inspiration for numerous writers in prose and poetry. It has been drawn upon in many different ways, forming sometimes the central theme of the work, or alluded to in more subtle ways.

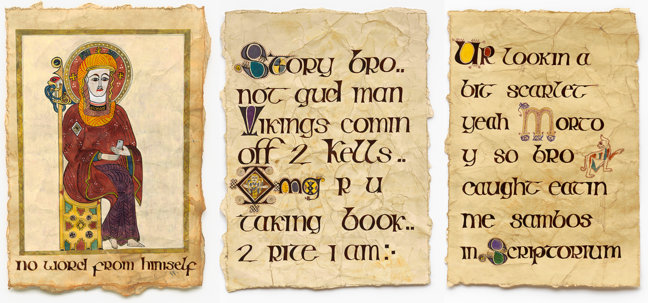

The ‘otherworldliness’ of the manuscript has seen it feature in a number of works of fantasy and science fiction. R.A. McAvoy’s, The Book of Kells (1985) uses the manuscript as the central theme of a fantasy, in which a modern-day couple time-travel back to medieval Ireland to avenge a Viking attack.

Fig 1. R.A. McAvoy’s. The Book Of Kells (1985), Fig 2. Guardians of the Galaxy ‘The Irish Wolfhound’.

Fig 1. R.A. McAvoy’s. The Book Of Kells (1985), Fig 2. Guardians of the Galaxy ‘The Irish Wolfhound’.

In the Marvel Comic’s Guardians of the Galaxy issue ‘The Irish Wolfhound’, the story again involves the manuscript. This time, it has been used by ‘The Calligrapher’ to write the definitive story of the invasion of the Martians that was soon to occur. It then disappears only to be rediscovered centuries later at Newgrange, from where it must be saved by the Guardians of the Galaxy.

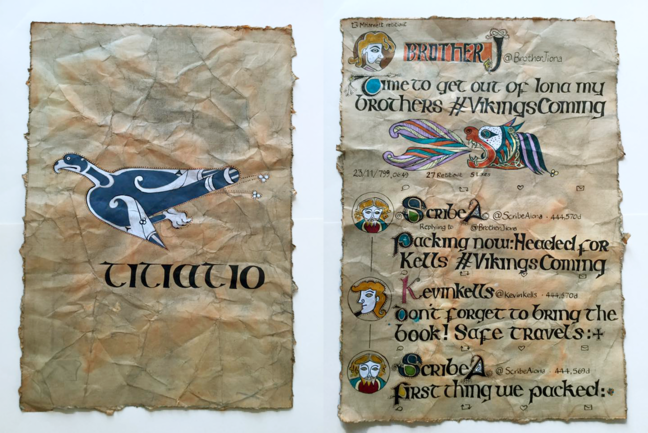

Fig 3. Deborah Lattimore’s, The Sailor who Captured the Sea: A Story of the Book of Kells (1991), Fig 4. Eithne Massey’s book based on the film The Secret of Kells (O’Brien Press, 2009).

Fig 3. Deborah Lattimore’s, The Sailor who Captured the Sea: A Story of the Book of Kells (1991), Fig 4. Eithne Massey’s book based on the film The Secret of Kells (O’Brien Press, 2009).

In children’s literature, the story of the making of the book, during turbulent times of Viking attack is the setting for both Deborah Lattimore’s, The Sailor who Captured the Sea: A Story of the Book of Kells (1991) and Eithne Massey’s book based on the film The Secret of Kells (O’Brien Press, 2009).

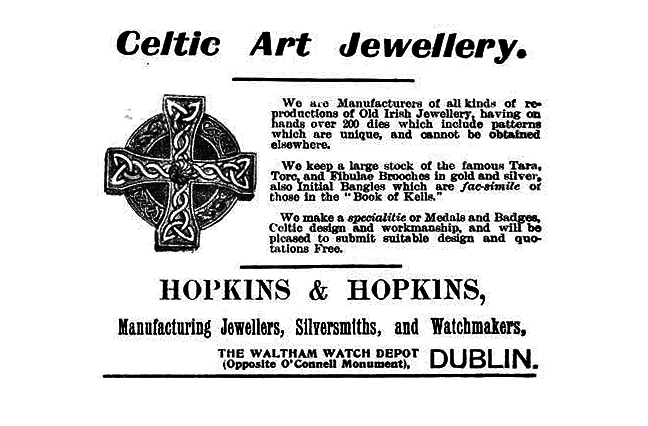

Fig 5. Bartholomew Gill’s, Death in Dublin. (Avon, 2002), Fig 6. Ian Wild’s Short Story, The Woman who Swallowed the Book of Kells. (Fish Publishing, 2000).

Fig 5. Bartholomew Gill’s, Death in Dublin. (Avon, 2002), Fig 6. Ian Wild’s Short Story, The Woman who Swallowed the Book of Kells. (Fish Publishing, 2000).

Art theft is a common theme in the genre of thriller writing, and although thankfully it is over 1,000 years since the manuscript suffered this fate, it has happened more recently in fiction. The theft of Ireland’s greatest cultural treasure – and murder of the night watchman in the process – is the central theme of Bartholomew Gill’s Death in Dublin (Avon, 2002). This triggers a series of events that threaten to bring about the entire destruction of contemporary Irish Society. The disappearance of the manuscript is also the theme of Ian Wild’s Short Story, The Woman who swallowed the Book of Kells (Fish Publishing, 2000). In this case, as the title suggests, this is not the work of ruthless criminals, but of a woman with a penchant for (literally) eating biblical texts. The consequences of this particular meal however, precipitate an unexpected series of events when she returns home to her native Cork…

In the comments section below:

- Have you come across the Book of Kells in any fictional books or magazines you have read?

- How was the Book presented and what themes did it represent?

- If you haven’t come across the Book of Kells in this way, how would you present the Book in a work of fiction?