The Book of Kells as Irish icon

The Book of Kells as Irish icon

173 comments

As we have seen, throughout the nineteenth century, the numbers of visitors coming to see the Book of Kells were relatively modest, and publications of its artwork relatively few. So how did its fame spread so widely in the final decades of the nineteenth century? The answer lies in mass consumption, from the middle of the nineteenth century, for jewellery and other luxury goods to be produced in a revivalist or historical style.

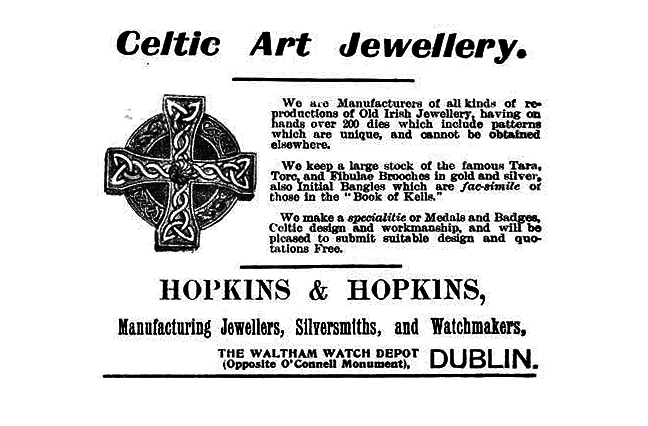

From at least as early as the 1840s a number of Dublin jewellery firms, including George Waterhouse and Co. and West and Sons, had begun to make copies of ancient brooches. The period coincided with the rise of the middle classes, and the beginnings of overseas tourism to Ireland, creating a new market with a particular interest in designs based on specifically Irish antiquities. The range of designs soon expanded and before too long letters from the Book of Kells (most likely based on the designs of Helen d’Olier) were appearing on bracelets and brooches created by the Irish jeweller Joseph Johnson.

Fig 1. An advertisement for some of the Celtic revival wares made by the jewellers Hopkins and Hopkins, including Book of Kells-inspired bangles. CC-PD.

Fig 1. An advertisement for some of the Celtic revival wares made by the jewellers Hopkins and Hopkins, including Book of Kells-inspired bangles. CC-PD.

The success of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 – a large public international exhibition aimed at showcasing ‘works of industry of all nations’ – preceded a series of World’s Fairs and exhibitions of culture and industry across Europe and the US. This provided the perfect forum for jewellers and other Irish craftspeople to show, and sell, their distinctively Irish art to a broader audience.

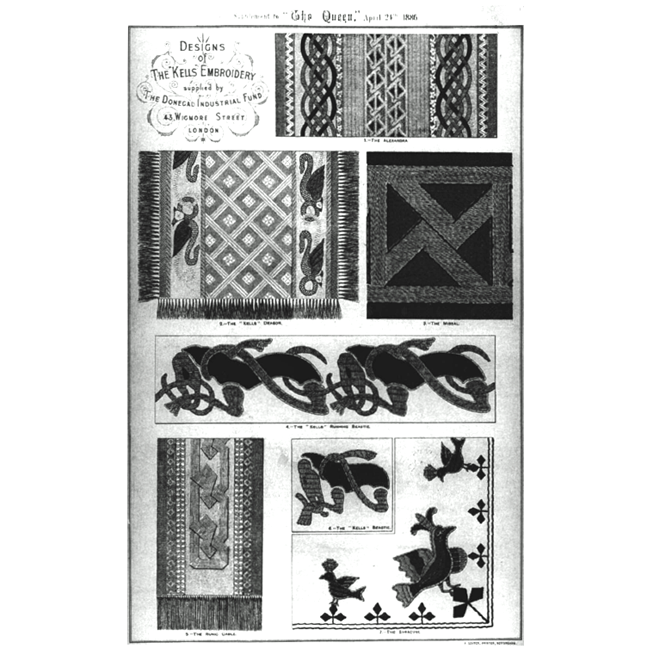

Among these were a number of groups who, inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement’s backlash against mass–production, had been formed to promote the use of native materials, such as wool, linen and lace, made by local artisans. For example, the Donegal Industrial fund, established in 1883 by Mrs Ernst Harte, taught local Donegal women how to spin and dye local woollen yarns and weave it into a style called ‘Kells embroidery’. Harte had visited the Book of Kells and turning its pages had

‘revealed to [her] a mine and storehouse of design. In a few square inches of these wondrous pages there was more design than in sheaves of original drawings turned out from South Kensington [art school]’. A decade after its foundation, these wares were on sale at a major stand in the Chicago World’s Fair.

Fig 2. Kells embroidery designs. In fact, inspiration for some of these designs comes from other early Irish works, including the Book of Durrow. CC-PD.

Fig 2. Kells embroidery designs. In fact, inspiration for some of these designs comes from other early Irish works, including the Book of Durrow. CC-PD.

Another collective, established in the early twentieth century by Evelyn Gleeson and Elizabeth and Lily Yeats – sisters of the poet W.B. Yeats – continued the tradition of creating quality hand crafted products drawing on ‘Celtic’ art, including the book of Kells, for inspiration. Among their masterworks are the embroidered textiles created for the Honan Chapel in Cork, all of which draw inspiration from images derived from the Book of Kells (most likely through the medium of Edward Sullivan’s book on the manuscript.

Fig 3. A cushion made by the Dun Eimear guild for the Honan chapel, Cork, based on the symbol of St John from fol. 27v. Honan chapel collection, University College Cork.

Fig 3. A cushion made by the Dun Eimear guild for the Honan chapel, Cork, based on the symbol of St John from fol. 27v. Honan chapel collection, University College Cork.

In more recent years the role of imagery from the Book of Kells as Irish national symbols has been consolidated by its use on the 2p coin, on part of the £5 note and a special issue 20 euro coin in 2012, as well as on national postage stamps. Its distinctive artwork continues to appear in great variety on a wide range of souvenirs – not all always adhering to the same Irish-made fine quality promoted in the early years of their production.

Fig 4. An Irish 2 pence coin. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 5. A special issue €20 coin. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 6. An Irish £5 note. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 7. Irish postage stamps. © An Post.

Fig 4. An Irish 2 pence coin. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 5. A special issue €20 coin. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 6. An Irish £5 note. © Central Bank of Ireland. Fig 7. Irish postage stamps. © An Post.In the comments section below:

• Why do you think the artwork of the Book of Kells became such a popular theme in consumer goods?

• Do you think its popularity will continue this way in the future?

© Trinity College Dublin

Postar um comentário