Pigments in the Book of Kells

John Gillis is a conservator in the library at Trinity College, specialising in vellum. He's worked on a number of early Irish manuscripts, including The Faddan More Psalter, giving him a unique insight into how these manuscripts were made. The production of parchment, or vellum, is historically ancient and the use of it as a writing substrate harks back to kind of the development of the codex, or the book form as the Book of Kells is. Basically, it's produced from an animal pelt, where they would flay the animal. In the case of Kells, it's calfskin. If we look at what we've got here, this is the full pelt of a very young calfskin.

And it's a natural product, so it has, unlike paper -- which you can control, and you can create a uniform end product -- with a natural product like a skin, then you don't have that sort of control. So it retains a lot of its features -- anatomical features, if you like -- because there is the area where the tail was. There's the clear feature, the marking of the spine, which of course runs from one end to the skin to the other. And there's the axilla, where the legs and neck are. And these all create particular features within the skin. We're rarely this lucky, as to find the evidence that easy.

But there you can clearly see this is a part of a skin. Obviously, it's not a full skin. This is a goat skin. But you can clearly see the impact of the spine on the skin. And we even see it on one of the illuminated pages, the portrait of Matthew. As I say, it's that sort of evidence that we look for and it gives us an idea of how they laid out the manuscript, how they designed the manuscript, before they put it together. But the actual physical preparation of the skin then involved obviously folding it into what we call a bifolium. So a fold that you see inside a book -- like this.

So these folded sheets are inserted into each other, and create what we call a quire. So again, there can be conventions in how this is done. So a number of folders inserted into each other create a quire. You basically had a series of gatherings. In the Book of Kells, for example, there are 38 of these quires. So you've got quires of various folio counts-- fours and twelves. And then they're gathered together-- literally assembled together. And they're sewn together by a sewing support, through a back fold. In the case of Kells, we have no evidence of the original structure -- because of damage, because of rebinding over the years.

It's estimated the Book of Kells has had up to five rebinding over that period of time. So as a result of all this interference, we've lost evidence of what was possibly the original structure. But basically what they're doing is, they're sowing one quire to the next -- either with an additional support on the spine, or possibly without, just using the threads. In effect, it's a single length of thread running the entire length of the book. You know, quite a feat when you think about it. Obviously, they're adding on threads as they sew along. But with Kells, the end product was a considerable end product. And you can see it here.

John Gillis is a conservator in the library at Trinity College, specialising in vellum. He's worked on a number of early Irish manuscripts, including The Faddan More Psalter, giving him a unique insight into how these manuscripts were made. The production of parchment, or vellum, is historically ancient and the use of it as a writing substrate harks back to kind of the development of the codex, or the book form as the Book of Kells is. Basically, it's produced from an animal pelt, where they would flay the animal. In the case of Kells, it's calfskin. If we look at what we've got here, this is the full pelt of a very young calfskin.

And it's a natural product, so it has, unlike paper -- which you can control, and you can create a uniform end product -- with a natural product like a skin, then you don't have that sort of control. So it retains a lot of its features -- anatomical features, if you like -- because there is the area where the tail was. There's the clear feature, the marking of the spine, which of course runs from one end to the skin to the other. And there's the axilla, where the legs and neck are. And these all create particular features within the skin. We're rarely this lucky, as to find the evidence that easy.

But there you can clearly see this is a part of a skin. Obviously, it's not a full skin. This is a goat skin. But you can clearly see the impact of the spine on the skin. And we even see it on one of the illuminated pages, the portrait of Matthew. As I say, it's that sort of evidence that we look for and it gives us an idea of how they laid out the manuscript, how they designed the manuscript, before they put it together. But the actual physical preparation of the skin then involved obviously folding it into what we call a bifolium. So a fold that you see inside a book -- like this.

So these folded sheets are inserted into each other, and create what we call a quire. So again, there can be conventions in how this is done. So a number of folders inserted into each other create a quire. You basically had a series of gatherings. In the Book of Kells, for example, there are 38 of these quires. So you've got quires of various folio counts-- fours and twelves. And then they're gathered together-- literally assembled together. And they're sewn together by a sewing support, through a back fold. In the case of Kells, we have no evidence of the original structure -- because of damage, because of rebinding over the years.

It's estimated the Book of Kells has had up to five rebinding over that period of time. So as a result of all this interference, we've lost evidence of what was possibly the original structure. But basically what they're doing is, they're sowing one quire to the next -- either with an additional support on the spine, or possibly without, just using the threads. In effect, it's a single length of thread running the entire length of the book. You know, quite a feat when you think about it. Obviously, they're adding on threads as they sew along. But with Kells, the end product was a considerable end product. And you can see it here.

Vellum and the making of a book

184 comments

During the early medieval period in Western Europe, parchment or young animal skins were the preferred writing surface for manuscripts.

We explore some of the characteristics of the material, and how it was cut down and sewn together to create the book form with which we are so familiar today.

© Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin

184 comments

During the early medieval period in Western Europe, parchment or young animal skins were the preferred writing surface for manuscripts.

We explore some of the characteristics of the material, and how it was cut down and sewn together to create the book form with which we are so familiar today.

© Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin

Voices of Irish scribes

It was not uncommon for Irish scribes to take a break from the copying of texts to make comments on their materials, excuse the poor quality of their work, or make reference to the events going on around them. These ‘marginalia’, usually written in the vernacular Irish give us an insight into their lives.

The bitter wind is high tonight, it lifts the white locks of the sea; in such wild winter storm no fright of savage Vikings troubles me.

St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 112. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

‘the vellum is defective, and the writing’

St Gallen Priscian St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p.195. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

‘This page has not been written very slowly’

St Gallen Priscian St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p.195. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

‘Of Patrick and Brigit on Máel Brigte, that he may not be angry with me for writing that has been written at this time’

St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 202. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

‘A hedge of trees surrounds me: a blackbird’s lay sings to me – praise which I will not hide – above my booklet the lined one the trilling of the birds sings to me. In the grey mantle of the beautiful chant sings to me from the top of the bushes: may the Lord protect me from Doom. I write under the greenwood’.

St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 203. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

‘massive hangover’

St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 204. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.

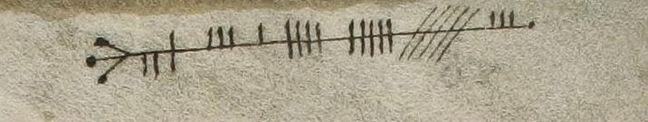

Fig 1. Marginal note in ogham script that reads Ale [Lait] + killed [ort], i.e. an ale-induced hangover. St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 204. CC-BY-NC

‘New parchment, bad ink, O I say nothing more’

St Gallen Priscian St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 214.

‘The last column of writing was completed with three dips of the pen’

Book of Armagh, Dublin TCD MS 52, fol. 78r. Ninth-century New Testament and saints lives, Armagh.

‘God bless my hands today’

Cassiodorus in Psalmos, Laon MS 26, f18v. Early ninth-century by an Irish scribe.

‘Pray for Maelbrigte, who wrote this book in his 28th year’

British Library, Harley 1802, fol. 127v. Written in Armagh, 1138AD.

‘Had I wished, I could have written the whole commentary like this’

Written in tiny letters on a slip of vellum between two folios. British Library, Harley 1802. Written in Armagh, 1138AD.

‘the cat has gone astray’

Leabar Breac, RIA MS p. 164. Historical miscellany.

‘May God forgive Edmund the putting of colour on this book on the eve of Sunday’

Oxford, Bodleian, MS Laud. 610, fol. 116r. Historical miscellany, late fifteenth century, Counties Kilkenny and Tipperary.

‘the phlegm is upon me like a mighty river, and my breathing is laboured.’

Egerton 88 fol. 26, Law tract by Law tract Domhnall O Duibhdabhoirenn, c. 1564, Co. Clare.

‘blood from the finger of Maelaghlin’

Note beside a blood stain, Dublin, Kings Inns MS 16, fol 5v. 16th century Irish medical text.

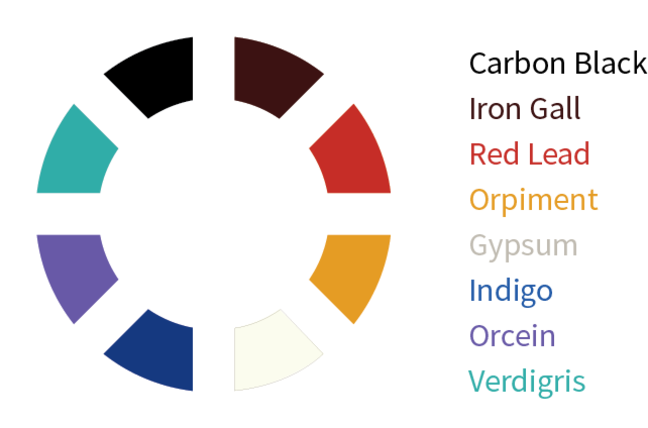

Susie Bioletti is keeper of conservation and preservation in a library at Trinity College. Over the past few years, she's been conducting research into the inks and pigments made to create early Irish manuscripts. The brilliance of the colours in the Book of Kells has fascinated people through the centuries, and there's been a lot of discussion about what those products might be. So coming to the present day, we're really fortunate in that we have technologies available now to use for manuscripts such as the Book of Kells, which are absolutely nondestructive and noninvasive. So here in Trinity, the two techniques that we've had available have been Raman spectroscopy, which is widely used for pigment analysis. And we also use X-ray fluorescence.

In combination, they're quite powerful tools because you can support the evidence you get from one piece of equipment with the results from another. And both of them are used directly onto the manuscript, and we get instant results. They'll tell us information about the chemistry of the pigment, and from that, we then have to do some detective work in matching the chemical profile back to the colour. So at the end of the work that we've carried out here, we've narrowed the pellet down to 10 pigments. So the pigments that we have on the manuscript have been created from a number of different products, from dye stuff extracted from plants, from minerals that have been ground and pulverised.

And they've also been created or manufactured from products and transformed into another product. So we have lichen producing a purple pink dye, which is identified on the manuscript as our principal purple. The dye would have to be extracted from this. So the principal ink is an ink known as iron-gall ink and this was created by extracting a gallotannic acid from an oak apple. And that would have been pulverised and soaked in water, then mixed with iron sulphide. And as it oxidises, a beautiful link is formed, which has a range of tones from quite warm brown to warm black. And along with a few other pigments, this black is the principal ink.

The brilliant yellow throughout the manuscript is in all cases a product called orpiment. It's a mineral pigment, and it's incredibly toxic. The vibrant yellow is used in a manner that gold perhaps would have been used. Gold was used at this time on manuscripts. However, we have no gold used on this manuscript. It's the sheer brilliance of the orpiment that replicates the gold effect.

The vibrancy, beauty, application and combinations of colour in the Book of Kells has fascinated viewers through the centuries.

Determining what materials were used requires analytical work. We can only use non-destructive techniques as we have a policy of non-sampling, so the techniques need to be safe to use directly on the manuscript.

Originally it was thought that up to thirty different pigments were used, but we have narrowed down the number and discovered the very clever use of a small number of plant- and mineral- based pigments which are mixed with white to lighten them, or with extra binder to make them glossier, or layered to create the rich and colourful impression conveyed by the manuscript today.

Some of the most extensively used pigments in the Book of Kells (Bioletti et al. 2009).

Some of the most extensively used pigments in the Book of Kells (Bioletti et al. 2009).

Postar um comentário