Working practice

Who were the scribes?

153 comments

Admiration for great works of art during the medieval period was often expressed in supernatural or magical terms. A great gospel book was more likely to be described as the ‘work of angels’ or of a saintly hand than of a mere mortal. Indeed, a common theme of early Irish saints’ lives is the divine aid given to them or by them in the creation or completion of holy books. St Comgall of Bangor, for example, was said to have blessed the hand of a novice to transform his writing from ‘the scratching of a bird’s claw’ to brilliant calligraphy.

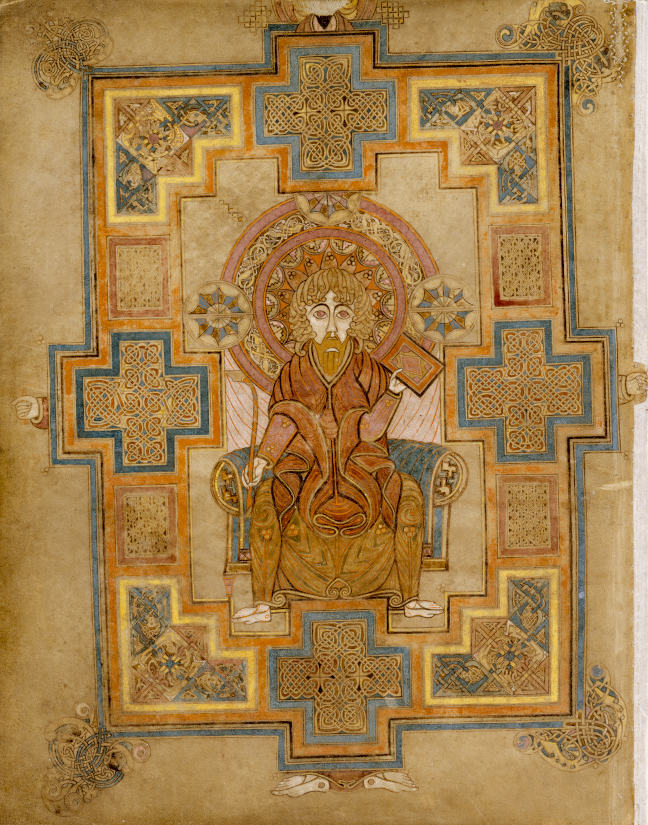

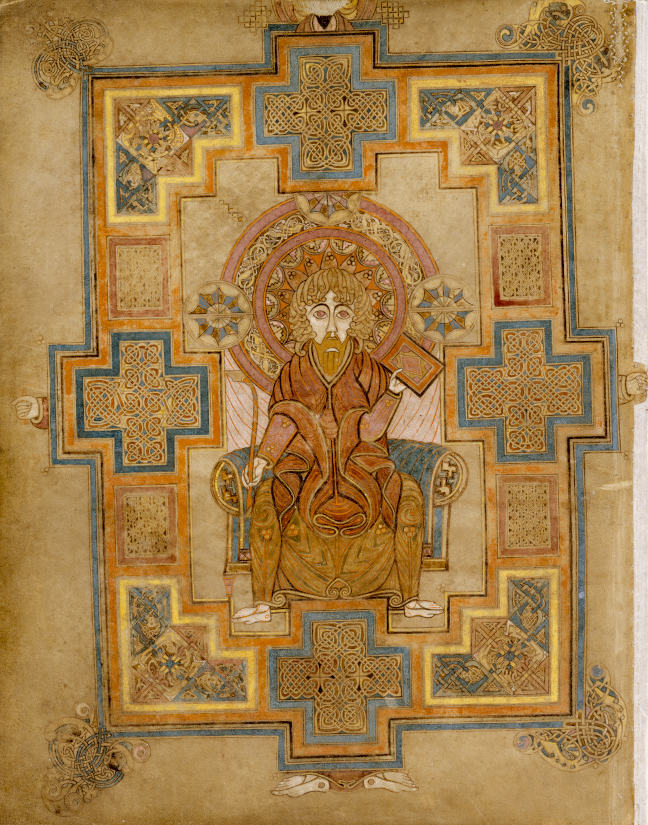

Fig 1. Fol. 291v The image of St John in the Book of Kells. As author of his gospel John holds a pen and has an inkwell at his foot. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

As a result of this, relatively few early Irish manuscripts preserve the names of their makers. Around 807AD a scribe called Ferdomnach, working in Armagh, recorded that he had worked on the Book of Armagh for the abbot of that monastery. He was clearly much-admired for his craft, as his death was recorded in monastic chronicle of 846 where he was described as a ‘sage and choice scribe’ of the church at Armagh. A note at the end of the MacRegol Gospels of around the same date asked the reader to remember in their prayers MacRegol, who both wrote and painted the book. This individual is thought to be the same ‘Macregol…scribe, bishop and abbot of Birr [Co. Offaly]’, whose death was recorded in 822.

Fig 1. Fol. 291v The image of St John in the Book of Kells. As author of his gospel John holds a pen and has an inkwell at his foot. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

As a result of this, relatively few early Irish manuscripts preserve the names of their makers. Around 807AD a scribe called Ferdomnach, working in Armagh, recorded that he had worked on the Book of Armagh for the abbot of that monastery. He was clearly much-admired for his craft, as his death was recorded in monastic chronicle of 846 where he was described as a ‘sage and choice scribe’ of the church at Armagh. A note at the end of the MacRegol Gospels of around the same date asked the reader to remember in their prayers MacRegol, who both wrote and painted the book. This individual is thought to be the same ‘Macregol…scribe, bishop and abbot of Birr [Co. Offaly]’, whose death was recorded in 822.

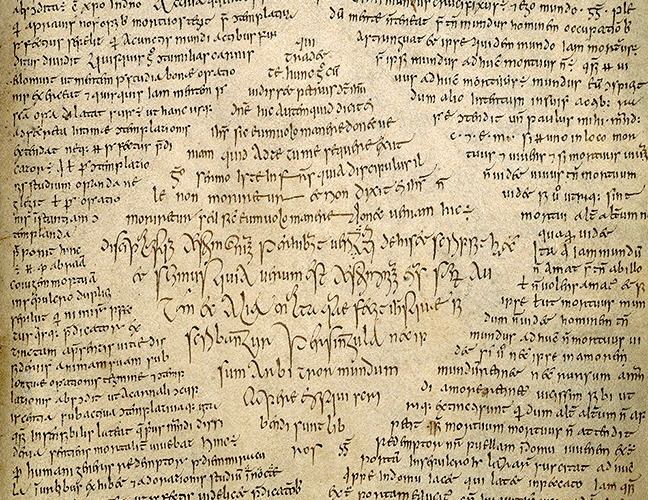

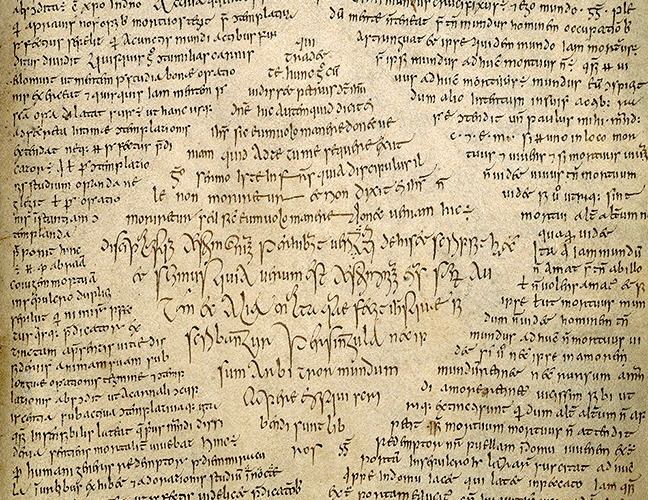

Fig 2. A sample of the handwriting of Ferdomnach, scribe of the Book of Armagh. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Such relative celebrity was, however unusual, and for most manuscripts, including the Book of Kells, the name or names of scribes remain unknown.

As both training and scribal practice was focused on copying, particular schools and scriptoria developed distinctive styles of calligraphy and decoration, making it often quite difficult to distinguish one hand from another. Some texts were compiled by one individual, others are collaborative works, with scribes working simultaneously on different quires (gatherings of folios) or, where pages were particularly densely ornamented, on separate leaves.

Despite much careful analysis of the pages of the Book of Kells, there remains disagreement as to how many scribes were involved. Some suggest that at least four were involved, each with their own particular expertise, while others have suggested that the Book was the work of just two individuals. Although sometimes the scribe was also responsible for the illustrations in a book, in the case of the Book of Kells it is thought that there were at least two or three specialist artists.

Although largely anonymous, we can gain some insight into the personality of early Irish scribes through comments, poems and drawings left by them in the margins of their manuscripts.

© Trinity College Dublin

Fig 2. A sample of the handwriting of Ferdomnach, scribe of the Book of Armagh. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Such relative celebrity was, however unusual, and for most manuscripts, including the Book of Kells, the name or names of scribes remain unknown.

As both training and scribal practice was focused on copying, particular schools and scriptoria developed distinctive styles of calligraphy and decoration, making it often quite difficult to distinguish one hand from another. Some texts were compiled by one individual, others are collaborative works, with scribes working simultaneously on different quires (gatherings of folios) or, where pages were particularly densely ornamented, on separate leaves.

Despite much careful analysis of the pages of the Book of Kells, there remains disagreement as to how many scribes were involved. Some suggest that at least four were involved, each with their own particular expertise, while others have suggested that the Book was the work of just two individuals. Although sometimes the scribe was also responsible for the illustrations in a book, in the case of the Book of Kells it is thought that there were at least two or three specialist artists.

Although largely anonymous, we can gain some insight into the personality of early Irish scribes through comments, poems and drawings left by them in the margins of their manuscripts.

© Trinity College Dublin

153 comments

Admiration for great works of art during the medieval period was often expressed in supernatural or magical terms. A great gospel book was more likely to be described as the ‘work of angels’ or of a saintly hand than of a mere mortal. Indeed, a common theme of early Irish saints’ lives is the divine aid given to them or by them in the creation or completion of holy books. St Comgall of Bangor, for example, was said to have blessed the hand of a novice to transform his writing from ‘the scratching of a bird’s claw’ to brilliant calligraphy.

Fig 1. Fol. 291v The image of St John in the Book of Kells. As author of his gospel John holds a pen and has an inkwell at his foot. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 1. Fol. 291v The image of St John in the Book of Kells. As author of his gospel John holds a pen and has an inkwell at his foot. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

As a result of this, relatively few early Irish manuscripts preserve the names of their makers. Around 807AD a scribe called Ferdomnach, working in Armagh, recorded that he had worked on the Book of Armagh for the abbot of that monastery. He was clearly much-admired for his craft, as his death was recorded in monastic chronicle of 846 where he was described as a ‘sage and choice scribe’ of the church at Armagh. A note at the end of the MacRegol Gospels of around the same date asked the reader to remember in their prayers MacRegol, who both wrote and painted the book. This individual is thought to be the same ‘Macregol…scribe, bishop and abbot of Birr [Co. Offaly]’, whose death was recorded in 822.

Fig 2. A sample of the handwriting of Ferdomnach, scribe of the Book of Armagh. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. A sample of the handwriting of Ferdomnach, scribe of the Book of Armagh. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Such relative celebrity was, however unusual, and for most manuscripts, including the Book of Kells, the name or names of scribes remain unknown.

As both training and scribal practice was focused on copying, particular schools and scriptoria developed distinctive styles of calligraphy and decoration, making it often quite difficult to distinguish one hand from another. Some texts were compiled by one individual, others are collaborative works, with scribes working simultaneously on different quires (gatherings of folios) or, where pages were particularly densely ornamented, on separate leaves.

Despite much careful analysis of the pages of the Book of Kells, there remains disagreement as to how many scribes were involved. Some suggest that at least four were involved, each with their own particular expertise, while others have suggested that the Book was the work of just two individuals. Although sometimes the scribe was also responsible for the illustrations in a book, in the case of the Book of Kells it is thought that there were at least two or three specialist artists.

Although largely anonymous, we can gain some insight into the personality of early Irish scribes through comments, poems and drawings left by them in the margins of their manuscripts.

© Trinity College Dublin

Working practice

The preparation of the parchment for script and painting was a complex and carefully thought through process.

First the quires were prepared and loosely held together with a temporary stitch to ensure that the position and flow of the text across the folio would be kept in order. In a quire with 4 bi-folia the first two pages and seventh and eighth pages of the text are written on the same folded piece of parchment. Then the outer margins of the text would be determined and the position of the lines marked with the point of a knife or a prick mark from an awl, or small pointed tool. These marks are visible on many pages at both the beginning and end of script lines. Guide lines for the scribe were ruled between the prick marks with a hard-point, a sharpened bone perhaps, leaving an impression rather than a drawn line.

Fig 1. The line endings of fol. 76v are clearly shown by a series of prick marks. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 1. The line endings of fol. 76v are clearly shown by a series of prick marks. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The script was kept very uniform with the words and decoration evenly positioned to the left and right margins to maximise the use of the vellum and create a harmony and precision for which the manuscript is renowned. The number of lines of script per folio ranges from 17 to 19. The order of script and paint application seems to have been organised so that script was completed first, leaving the pages ready for decoration. This way the script and decoration could be completed by the same hand, or with two scribes working closely together.

Fig 2. Detail of a lion on fol. 111r Showing how it has been added after the script. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. Detail of a lion on fol. 111r Showing how it has been added after the script. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Several folios in the Book of Kells are incomplete and others have unfinished details, which provide us with useful evidence of working practice. This visual evidence indicates that the preparation for intricate design elements was extremely well planned, providing complex patterns to guide the application of pigment. Under-drawing or guidelines, which are revealed in damaged areas as well as unfinished passages, were created with iron gall ink and strengthened as the design was built up. The ink was also used to articulate features, to provide outline to form, as well as to mark the boundaries for the application of the coloured details.

Fig 3. Detail from canon table on fol. 2r. Pigment has flaked away revealing preparatory drawings below. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 3. Detail from canon table on fol. 2r. Pigment has flaked away revealing preparatory drawings below. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Compasses and straight-edges were readily used for design layout along with free-hand line-work. A good example of this in the Book is in the script for fol. 29v. The script has been completed, and the position of the border decoration has been indicated by lines lightly ruled in iron gall ink. Using this scheme a scribe and an artist could work together to complete the page.

Fig 4. Lines of text from fol. 29v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 4. Lines of text from fol. 29v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin. Fig 5. Detail of fol. 29v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 5. Detail of fol. 29v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Folio 30v is also unfinished. Here the decoration is beginning to take shape, with the pigment applied between the lightly drawn outlines. These outlines would be strengthened as the design was completed, with the brown-black script ink also serving as a pigment and a dark accent to the bright colours.

Fig 6. Detail of fol. 30v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 6. Detail of fol. 30v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The full-page illuminations were created on single sheets of parchment and attached to the text quire, which meant they could be created independently and by a different scribe/artist. These were typically painted on one side only, with the verso or back of the page kept blank. Because of this we have been able to detect the markings used in the preparation of the design. For these picture pages sharp points were used to mark the ends of design elements that were then ruled with a straight-edge. Circles and semi-circles were drawn with compasses, which left fine pin-pricks at the centre of the diameter. The eight circle cross page exemplifies this with compass marks present in the centre of all circles, and pin marks at the start and finish of all ruled lines.

Fig 7. Fol. 33r A complex design used to preface Matthew 1:18. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 7. Fol. 33r A complex design used to preface Matthew 1:18. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin. Fig 8. Detail of fol. 33v showing the compass marks used to layout the design on the other side of the page © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 8. Detail of fol. 33v showing the compass marks used to layout the design on the other side of the page © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

They are also evident in the portrait of St John (fol. 291v) where the artist has used a compass to mark the centre point to the halo and all surrounding semi-circular patterning, with lines pricked and ruled to locate adjacent elements.

Fig 9 and 10. Details of fol. 291r the back of the portrait of John. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 9 and 10. Details of fol. 291r the back of the portrait of John. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.In the comments section below

- The Book of Kells originally had around 700 pages (we are not sure of the exact number).

- Thinking about the different elements that went in to creating the book, how long do you think it might have taken to make?

- What factors would you have to consider?

© Trinity College Dublin

Postar um comentário