The meaning of images in the Book of Kells

Flaws and imperfections

144 comments

One would expect such an important, high-class object as the Book of Kells to be made of the best materials and to have been flawless in both text and illustration, but this is not the case.

It is estimated that up to 159 calfskins would have been used in the production of the Book of Kells. Difficulties in procuring such a large quantity of high quality vellum resulted in sheets of uneven thickness and colour being used. As one turns the pages of the manuscript, there are noticeable differences in colour and thickness between the pages. In addition to this, some of the pages contained flaws. Rather than discard these, the scribes either worked around them, or simply patched them before proceeding with their work. There is a good example of this on fol. 316, where quite a large patch was stitched onto the page.

Fig 1. Patch on fol. 316v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Copying an entire gospel book in neat majuscule hand required effort and concentration. From time to time the scribes evidently became distracted, either skipping words by mistake (fol 146v), or in the case of fols. 218v and 219r, the same text has been transcribed twice.

Fig 1. Patch on fol. 316v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Copying an entire gospel book in neat majuscule hand required effort and concentration. From time to time the scribes evidently became distracted, either skipping words by mistake (fol 146v), or in the case of fols. 218v and 219r, the same text has been transcribed twice.

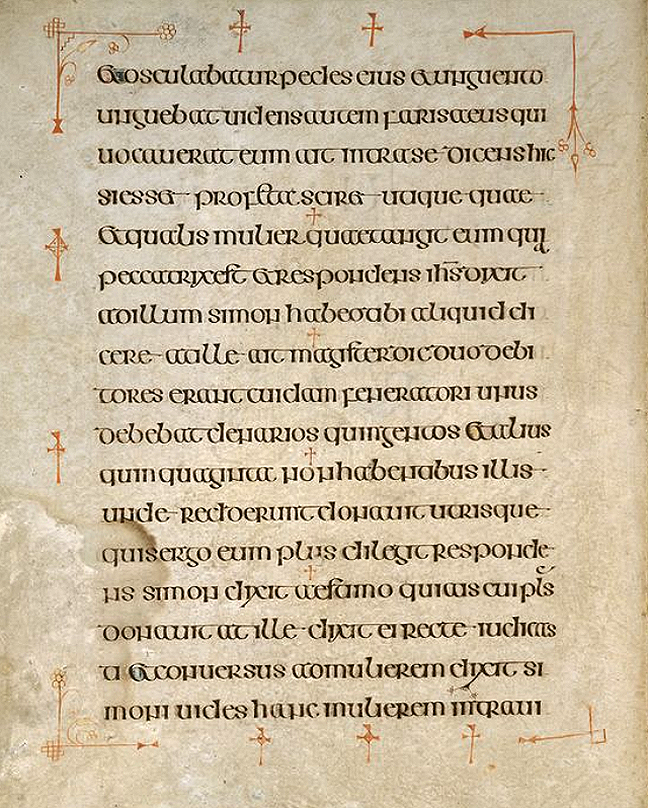

Fig 2. Fol. 146v a significant portion of text accidentally omitted has been added to the end of the page. A dotted red cross seven lines down indicates where the text belongs. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. Fol. 146v a significant portion of text accidentally omitted has been added to the end of the page. A dotted red cross seven lines down indicates where the text belongs. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

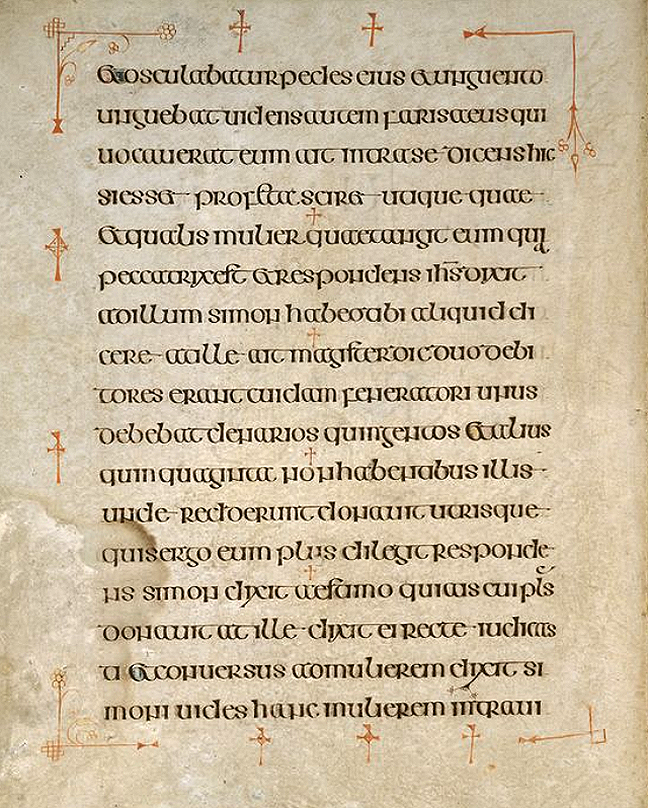

Fig 3. The text on fol. 218v is surrounded by red crosses and lines to indicate that it should be ignored as the text is repeated on the following page. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The copy is also only as good as its model. When transcribing the canon tables (a system that allows links to be made across each of the four gospels, we will be looking at this in more detail next week) the Book of Kells artists appear to have used a flawed model. Rather than being a practical aid to navigating the text, their function in this manuscript is purely decorative.

A small number of pages have also been left unfinished. Most obvious among these are the passages at the start of the Gospel of Matthew that outline the genealogy of Jesus Christ (Matthew 1:1-17) on fols. 29v – 31v. On fol. 30v for example, the text has been transcribed, and the outline of the frame of the page scored into the vellum. The scribe/artist had also started to draw in details and to paint them, but both drawing and painting are unfinished giving a useful insight into working practice.

It is not known why this section was never finished. There have been several suggestions. Perhaps it needed to be bound into the book in a hurry, or perhaps it was intentional, as perfection could only be achieved by God, and not within a man-made thing.

Fig 3. The text on fol. 218v is surrounded by red crosses and lines to indicate that it should be ignored as the text is repeated on the following page. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The copy is also only as good as its model. When transcribing the canon tables (a system that allows links to be made across each of the four gospels, we will be looking at this in more detail next week) the Book of Kells artists appear to have used a flawed model. Rather than being a practical aid to navigating the text, their function in this manuscript is purely decorative.

A small number of pages have also been left unfinished. Most obvious among these are the passages at the start of the Gospel of Matthew that outline the genealogy of Jesus Christ (Matthew 1:1-17) on fols. 29v – 31v. On fol. 30v for example, the text has been transcribed, and the outline of the frame of the page scored into the vellum. The scribe/artist had also started to draw in details and to paint them, but both drawing and painting are unfinished giving a useful insight into working practice.

It is not known why this section was never finished. There have been several suggestions. Perhaps it needed to be bound into the book in a hurry, or perhaps it was intentional, as perfection could only be achieved by God, and not within a man-made thing.

Fig 4. Fol. 30v part of the unfinished section of Matthew 1:1-17. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

© Trinity College Dublin

Fig 4. Fol. 30v part of the unfinished section of Matthew 1:1-17. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

© Trinity College Dublin

144 comments

One would expect such an important, high-class object as the Book of Kells to be made of the best materials and to have been flawless in both text and illustration, but this is not the case.

It is estimated that up to 159 calfskins would have been used in the production of the Book of Kells. Difficulties in procuring such a large quantity of high quality vellum resulted in sheets of uneven thickness and colour being used. As one turns the pages of the manuscript, there are noticeable differences in colour and thickness between the pages. In addition to this, some of the pages contained flaws. Rather than discard these, the scribes either worked around them, or simply patched them before proceeding with their work. There is a good example of this on fol. 316, where quite a large patch was stitched onto the page.

Fig 1. Patch on fol. 316v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 1. Patch on fol. 316v © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Copying an entire gospel book in neat majuscule hand required effort and concentration. From time to time the scribes evidently became distracted, either skipping words by mistake (fol 146v), or in the case of fols. 218v and 219r, the same text has been transcribed twice.

Fig 2. Fol. 146v a significant portion of text accidentally omitted has been added to the end of the page. A dotted red cross seven lines down indicates where the text belongs. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 2. Fol. 146v a significant portion of text accidentally omitted has been added to the end of the page. A dotted red cross seven lines down indicates where the text belongs. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin. Fig 3. The text on fol. 218v is surrounded by red crosses and lines to indicate that it should be ignored as the text is repeated on the following page. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 3. The text on fol. 218v is surrounded by red crosses and lines to indicate that it should be ignored as the text is repeated on the following page. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

The copy is also only as good as its model. When transcribing the canon tables (a system that allows links to be made across each of the four gospels, we will be looking at this in more detail next week) the Book of Kells artists appear to have used a flawed model. Rather than being a practical aid to navigating the text, their function in this manuscript is purely decorative.

A small number of pages have also been left unfinished. Most obvious among these are the passages at the start of the Gospel of Matthew that outline the genealogy of Jesus Christ (Matthew 1:1-17) on fols. 29v – 31v. On fol. 30v for example, the text has been transcribed, and the outline of the frame of the page scored into the vellum. The scribe/artist had also started to draw in details and to paint them, but both drawing and painting are unfinished giving a useful insight into working practice.

It is not known why this section was never finished. There have been several suggestions. Perhaps it needed to be bound into the book in a hurry, or perhaps it was intentional, as perfection could only be achieved by God, and not within a man-made thing.

Fig 4. Fol. 30v part of the unfinished section of Matthew 1:1-17. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Fig 4. Fol. 30v part of the unfinished section of Matthew 1:1-17. © The Board of Trinity College, University of Dublin.

© Trinity College Dublin

Next week: The meaning of images in the Book of Kells

Well done for reaching the end of Week 2 of our course. We hope you have enjoyed the videos and articles about the making of the Book of Kells.

Remember, if you would like to access more resources about this course, refer to the databank in Week 1.

Next week we will be exploring some of the most fascinating illustrations in the Book and the meaning behind them, including:

- Symbols such as the Chi Rho, the cross, and the lozenge

- The Virgin and Child page

- Eucharistic imagery

- The Evangelists

- Cats, fish and other animals

- The Temptation of Christ page

- The Arrest of Christ page

At the end of the week, you will get a chance to interpret a page and share your thoughts with other learners.

Join us in Week 3!

© Trinity College Dublin

Whether a painting in an art gallery or a meme, everyone has a different way of looking at images and also of understanding them. When you look at one of the great illustration pages of the Book of Kells, you might first see a figure staring out at you or a giant letter. The closer you look, however, the more detail you see, and layer upon layer of ornamentation are revealed. You might ask why is this here? What does it mean? There's no single answer to those questions. The Book of Kells has layers of meaning. But that's what we will be looking at this week. During the early medieval period, debate raged over the appropriate way to illustrate Christian art.

The core of the debate centred on the second commandment: thou shalt not make graven images, thou shalt not create a likeness of anything in heaven, or on the earth, or in the water, and thou shalt not bow down to it. Early Christian commentators took this literally and created a set of signs and symbols to reflect various religious ideas. However, over time, other commentators suggested that the most effective way to tell stories from the Bible or to help focus the devotion of Christians was through the illustration of the figures, the personalities within the Bible. The debate came to a fore around the eighth century, just around the time that the Book of Kells was being conceived.

In the east in the Byzantine Empire, the popularity of icons, or pictures of holy figures, had reached a peak to the extent that Christians were beginning to bow down in front of them to worship them as though they were actually the holy people themselves. And as such, it was decreed that these images should be destroyed as being contrary to the second commandment, and instead replaced with a set of signs and symbols. In the west, however, the figurative tradition lived on, with the appropriate form of representation seen to be figurative, again reflecting the stories of the Bible or likenesses of individual saints or holy people. The Book of Kells walks a line between these two traditions.

On the one hand, in its pages we find recognisable holy figures. But on the other, we find numerous signs and symbols in which much more imagination and ingenuity has been invested. And it's these that we'll be looking at in more detail. In his account of the poet monk Caedmon, Bede, a seventh century writer, speaks to us of the practise of ruminazione, like a chewing on the cud. It's a spiritual practise whereby someone thinks of a text and slowly allows it become part of whom they are. It's a bit like the cow with the four stomachs and the cud slowly going through the cow.

In the same way, the words were to slowly go through a person and become part of the person themselves. Similarly, there are images to be found in the Book of Kells, and these images can sometimes have very deep meanings. That meaning may be linked to the meaning of another image on the same page or a word. And again, when you put different images together, you can go to greater depths of understanding. The understanding of the image may vary depending on the context in which you see the image, or indeed, on the audience which is looking at the image and seeking to interpret it to go deeper into the text.

Of course, the ability to understand images -- to read them, if you like -- depends on the culture in which people understand those images and can read them like they'd read a word in a text. When we move outside that culture to a people who don't understand the images, or the artwork, the art symbolism, then we've got to ask, is it still of use? Well, we know it is. Because just a few decades before the Book of Kells was created, Boniface went as a missionary to Germany. And before he went he asked that he carry with him a New Testament written in gold lettering so that it might visibly make manifest the importance of the message it contained.

In other words, precious materials and art help to communicate to people the important message which the book contains. Precious materials like gold weren't used in the making of the Book of Kells. However, the range of brilliant colours and the intricacy of its illuminations still leave us in awe. Little wonder, then, that since early times the Book of Kells has been considered to be the work of supernatural forces, whether by the hand of St. Columcille himself or the work of angels.

Everybody looks at and understands images slightly differently. The images in the Book of Kells are no different. Your first impression when you see one of the more densely painted pages of the Book may be simply of the overall form – a figure staring out from the page, or a giant letter emerging from a tangle of pattern. But the longer you look, the more you will see and wonder what it all means.

The art of the Book of Kells combines two traditions current in Christian art of the early medieval period. One, which engaged images of holy figures to tell a story, or convey a certain idea, the other, which used symbolic means. Just as scholars of the Bible were encouraged to meditate on its text, the scale and density of decoration in the Book of Kells was probably intended to perplex, and to encourage the reader to stop and meditate on the meaning, or meanings, that it held.

Coming up

This week we will be exploring a range of different illustrations within the Book of Kells including symbols, animals, and religious imagery. At the end of the week, we will be asking you to interpret a page from the Book.

Don’t forget to consult the glossary which explains some of the key terms used in the course.

© Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin

Postar um comentário